With more than 100 million fans expected to tune in to watch Super Bowl 50 on TV, and attendees paying thousands of dollars to be at the game in Santa Clara, California, on Sunday, all the excitement puts a spotlight on football’s status as a mega-business — a $45-billion-a-year one.

While big games and winning seasons are emotional highs for die-hard fans, they are monetary assets for owners. Longer seasons and higher attendance rates translate to more revenue, and winning teams can often fetch richer sponsorship deals.

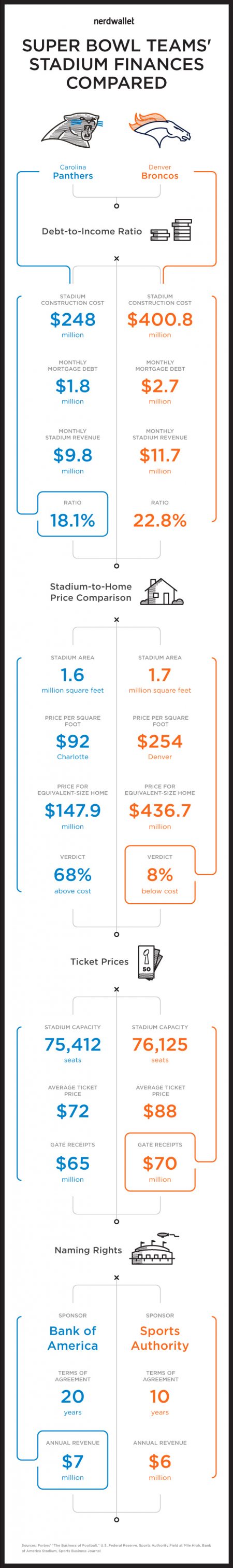

That got us wondering whether Super Bowl opponents the Denver Broncos and Carolina Panthers bring in enough to cover the cost of their stadiums, which are used for two preseason and eight regular-season home games a year — not counting playoff games. Just for fun, we took an in-depth look at the economics of each franchise’s largest investment: its stadium.

Stadium ‘mortgage’ matchup

Treating stadium revenue as income and construction costs as mortgage debt, we calculated what the debt-to-income ratio would be for stadiums if they were the “homes” of their teams, which had to pay off their debt the way individuals pay off a 30-year mortgage. The debt-to-income ratio is a comparison of a person’s monthly debt payment to his or her monthly income. The lower the ratio, the more a stadium is worth its mortgage price. Conventional wisdom says individuals should not exceed a 33% debt-to-income ratio.

To further determine the financial health of the Super Bowl participants, we looked at the median price per square foot of homes in Denver, Colorado, and Charlotte, North Carolina, and examined whether their stadiums were built below or above cost, as compared with an ordinary home. Lastly, we broke down stadium revenue into the two largest components: ticket sales and naming rights.

Here’s how the Panthers and the Broncos stack up in terms of which team’s stadium investment earns the title of paying off the most.

Notes on methodology

Stadium construction costs, capacity, and ticket prices and gate receipts for the 2014-15 season came from the annual evaluations done by Forbes’ “The Business of Football.” Annual interest rates for 30-year fixed mortgages came from the U.S. Federal Reserve. Stadium square footage came from the websites of stadiums themselves. Details on naming rights came from Sports Business Journal.

To calculate monthly mortgage costs, we used a 30-year fixed rate, treating the construction cost of a stadium as the principal, and the historical interest rate for the year the stadium opened. To get stadium revenue, we calculated “local revenue” based on statistics from “The Business of Football.” Special thanks to professor Victor Matheson of the College of the Holy Cross, who consulted on stadium financing.

Kamran Rosen is a data analyst at NerdWallet, a personal finance website. Email: kamran@nerdwallet.com.

Image of Denver’s Sports Authority Field at Mile High via iStock.

No comments:

Post a Comment